Soon, it was time for Kai Chang to return to Malaya. Kai Chang’s mother entrusted her chambermaid to the newly wed’s care. Kai Chang decorously adopted her as his daughter. He harboured a hope of more visits home or even maybe just maybe to convince his parents to migrate to his new home. However, fate had been known to be cruel, and it was truly cruel for Kai Chang. Unbeknownst then, he was bidding farewell to his parents for the last time. His hope was never to be fulfilled.

He would have spent longer than the 5 months with his parents had he known that the memory of them hugging at the pier with tears streaming down their cheeks would be their last. Such thoughts would well up tears each time Kai Chang reminisced of home. He lost both parents to the war…yes, damn that damned war.

Upon his return to Sungai Petani, Kai Chang together with fellow clansmen from neighboring towns founded the Central Kedah Coffee Shop Owners Association and Ong Family Association the same year. Most, if not all, coffee shops in Sungai Petani were owned and managed by fellow clansmen who were all related by familial ties to Kai Chang. They took pride in the coffee they brewed. They guarded the secret of roasting coffee beans zealously. They valued familial ties above all else. They were stubbornly clannish….they were unquestionably Foochow.

It was almost midnight when Kai Chang’s anxious wait was relieved by a gutsy cry of baby boy, his firstborn, Haw Choo. Had he been patient a minute longer, Haw Choo would have celebrated his 19th birthday together with the independence of his birth country.

Another son and daughter followed in quick succession, adding to Kai Chang’s growing responsibility over his adopted daughter, two younger brothers and their families and his workers, all of whom migrated to Malaya under his sponsorship. Kai Chang unquestionably assumed the responsibility as the patriarch for the extended Ong family in Malaya. To shoulder such responsibility was to smother his first thought of joining the Resistance when he heard that the Japanese Imperial Army, specifically the 5th Division, had landed on the beaches of Pattani and Songkla, Thailand.

It must be the same accursed 5th Division that was engaged in see-saw battles with the Nationalist Kuomintang for the control of Fuzhou during the Sino-Japanese War of 1937, which took the lives of his parents. He broke down and cried for the whole week when he received the dreadful news a week prior to that fateful 7th December day of infamy.

The RAF aerodrome at Sungai Petani home base for the 21st RAAF fighter squadron and 27th RAF bomber squadron was bombed by Japanese high altitude bombers on the very first day of invasion. The town which was situated some 2 km away shook when the aerodrome fuel depot exploded from a lucky direct hit from the bombers. Most of the Brewster Buffalo fighters and Bristol Blenheim bombers were destroyed on the ground and the airfield was rendered inoperative. The British lines at Jitra and Gurun faltered and fell in quick succession, and Sungai Petani was deemed indefensible.

After Operation Matador, a full-scale Division-size pre-emptive strike into Thailand was cancelled by politicians half a globe away, the 11th Indian Infantry Division moved back into their defensive positions around Jitra, Kedah.

A secondary plan, 3-column mini Matador, namely Krohcol, Laycol and an armoured train, was hastily devised to delay the Imperial Army long enough for the fortification around Jitra to be completed. Mini Matador managed to secure a day or at most two for the soldiers in the trenches around Jitra before the vanguard of the Imperial Army appeared, just 3 days from their landing.

With ill-prepared defences extending over 23 km, the overstretched British were no match for the highly motivated and battle hardened Imperial Army. Their long defence line over a rather flat terrain to avoid flanking maneuvers lacked depth for an attritional defence. Tactically, Jitra was an indefensible position. The imperial Army merely needed to punch through at any point and the whole line would collapse. Out flanked, out maneuvered and out fought, the British were swiftly routed, costly in terms of men and material of war, and time.

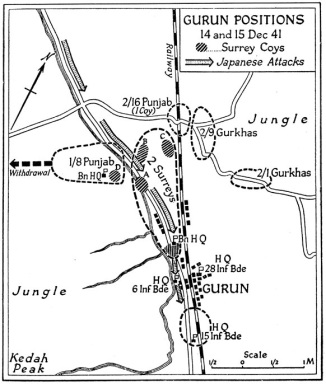

They hurriedly fell back to the next line of defence some 3 km north of Gurun, where both the north-south main trunk road and railway funneling into a natural bottle neck forming a much narrower front, ideal for defensive enfilading fire, a nightmare killing field for the Imperial Army. From Kedah Peak, one could observe any movements around her, even all the way north to southern Thailand. With their left flank protecting the main trunk road at the base of the impregnable Kedah Peak while the right flank the railway crossing at Guar Chempedak, they dug in and waited.

They did not have to wait long for in the twilight of dawn on 14th December Japanese light tanks probed and steamrolled down the trunk road. The tanks easily punched through the British left flank despite valiant defence. The defenders were simply out gunned for they had no anti-tank guns. The promised air cover could not take off from its base at Sungai Petani.

They fought gallantly but watched in horror when their bullets were merely ricocheting off the lightly armoured tanks. Their defensive positions quickly crumbled the following day, and the defenders hastily withdrew in utter confusion, hightailing more than 250 km all the way south to the next defensive position at Slim River, Perak.

Had General Percival decided to fortify the defensive positions at Gurun earlier instead of Jitra, the Imperial Army would have been given some bruising. They may even be stopped on their tracks with a few well placed anti-tank guns and some air cover, and the Battle of Gurun would have gone down the annals of history as Malaya’s very own Battle of Thermopylae.

General Percival’s initial fear that such an early and long retreat from Jitra without a fight to consolidate at Gurun would demoralize both his soldiers and the civilian population was proven recklessly moot. A tactical folly that would force him to hastily abandon more than 350 km stretch of land over Perlis, Kedah, Penang and Perak to the Imperial Army.

Kai Chang cursed when he saw the rag tag British Army and Airforce withdrew south. The town’s remaining garrison of British and Sepoy soldiers, the 11th Indian Infantry Division under the command of Major Gen David Murray-Lyon together with all war equipment were trucked south through Jalan Ibrahim before his very eyes without any military pomp or pageantry. They merely stared ahead unseeingly with defeat in their eyes. They were downcast and demoralized for they had been badly mauled at Jitra and Gurun. Kai Chang recognised some of them for they were his regular customers.

Kai Chang punched his white-knuckled fist defiantly into the air and screamed, “Hey, you are going the wrong way. The enemy is coming from the north.” His protest could not be heard, drowned by the drone overhead. The drone from the remaining Brewster Buffalo fighters and Bristol Blenheim bombers flying in similar cowardly direction was louder. Most probably, they understood not Foochow dialect.

The whistle from the last evacuation train for the remaining Europeans at dusk pierced the eerie silence. Even the nightly nature’s orchestra was silent. The local populace had been abandoned. That night was depressive thick with fear. They had heard of atrocities committed by the bestial Japanese Imperial Army in China, especially Nanjing. The much feared distant thunders of war had finally arrived. They cowered in gloom awaiting the impending doom.